PARADIM Highlight #117—In-House Research (2026)

David A. Muller (Cornell University)

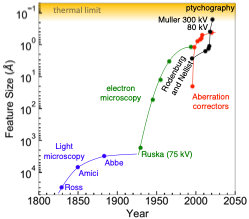

Being able to clearly see atoms and especially the atomic arrangement of defects is directly related to our ability to comprehend and design superior materials. Richard Feynman recognized this over 65 years ago in his famous There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom after-dinner speech. He bemoaned that the very best electron microscopes at the time had a resolution of about 10 Å and said, “What you should do in order for us to make more rapid progress is to make the electron microscope 100 times better.”

Figure 1: The ascent of microscope resolution is marked by paradigm shifts in design: (1) from light to electrons, (2) correction for lens aberration, and (3) a superior detector used together with ptychography. Muller’s work also notably marks the culmination of the ultimate branch of the resolution curve shown in black on the graphic.

David Muller did exactly this. His combining a new electron microscope pixel-array detector (EMPAD) that has incredible sensitivity and dynamic range with ptychography and multislice algorithms has led to the world’s highest resolution microscope. Prior microscopes were all limited in various ways by the optics of the microscope itself. In contrast, Muller’s images are limited by the thermal vibrations of the atoms themselves!

Much of this microscopy revolution occurred within PARADIM and has been made available to PARADIM users each step of the way. The electron microscope on which Prof. Muller established today’s highest resolution microscope world record is available to PARADIM (as are two newer instruments purchased by PARADIM together with matching funds from Cornell and the Kavli Foundation). His multislice ptychography algorithm was developed as part of PARADIM’s In-House research.

On February 10, 2026, the National Academy of Engineering elected David Muller to its Class of 2026 “For developing a new generation of electron detectors and reconstruction algorithms leading to the highest resolution electron microscope.”

It has long been recognized that the information limit set by diffractive optics is not an ultimate limit. Instead, there is phase information encoded throughout a diffraction pattern formed from a localized electron beam. It is in the form of interference patterns between overlapping scattered beams, and as the incident localized beam is scanned, the phase information and hence the interference patterns change in a predictable manner that can be used to retrieve the phase differences, an approach known as ptychography. While originally conceived to solve the phase problem in crystallography, ptychography has received renewed attention as a dose-efficient technique to recover the projected potential of materials, with modifications to measure finite thickness and three-dimensional samples. In principle. the resolution is limited by the largest scattering angle at which meaningful information can still be recorded, however, as electron scattering form factors have a very strong angular dependence, the signal falls rapidly with scattering angle, requiring a detector with high dynamic range and sensitivity to exploit this information.

To date, ptychography has been widely adopted for light and x-ray applications, yet the technique is still under-explored in transmission electron microscopy in large part because of the detector challenges. Traditional electron cameras such as charge-coupled devices (CCDs) and pixelated detectors have been hampered by slow readout speeds or poor dynamic ranges. Previous work has mainly made use of electrons only within the bright field disk and thus image resolution did not overcome the 2α limit imposed by the physical aperture. Based on decades of experience of detector development at CHESS, we developed and employ a new type of electron microscope pixel array detector (EMPAD) that is capable of recording all the transmitted electrons with sufficient sensitivity and speed to provide a complete ptychographic reconstruction. Our EMPAD design has a high dynamic range of 1,000,000:1 while preserving single electron sensitivity with a signal-to-noise ratio of 140 for a single electron at 200 keV. The detector retains a good performance from 20-300 keV. Here we operated at 300 keV with a maximum beam current of 33 pA. By utilizing essentially all collected electrons (99.95% of the incident beam), with a full 4D data set acquired in typically a minute, our full-field ptychographic reconstructions more than doubles the image resolution compared to the highest-resolution conventional imaging modes such as annular dark field STEM.

The work was recognized as the highest resolution microscope (of any type) by Guinness World Records in July 2018: https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/highest-resolution-microscope.

The new 0.2 Å resolution images were measured in 300-Å-thick PrScO3, and the multiple scattering was corrected using a multislice ptychography algorithm. The spatial resolution is now largely limited by the thermal fluctuations of the atoms themselves.

- Popular Science https://www.popsci.com/science/highest-microscope-resolution-individual-atoms/

- Cornell Chronicle https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2021/05/cornell-researchers-see-atoms-record-resolution

- Scientific American https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/see-the-highest-resolution-atomic-image-ever-captured/

- Y. Jiang, Z. Chen, Y. Han, P. Deb, H. Gao, S. Xie, P. Purohit, M. W. Tate, J. Park, S. M. Gruner, V. Elser, and D. A. Muller. “Electron Ptychography of 2D Materials to Deep Sub-Ångström Resolution,” Nature 559 (2018) 343–349. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0298-5;

- Z. Chen, Y. Jiang, Y. Shao, M.E. Holtz, M. Odstrčil, M. Guizar-Sicairos, D.G. Schlom, and D.A. Muller. “Electron ptychography achieves atomic-resolution limits set by lattice vibrations,” Science 372 (2021) 826-831. DOI: 10.1126/science.abg2533

D.A.M. thanks M. Humphry of Phasefocus for helpful discussions on multislice 3D ptychography. Funding: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DMR-1539918 (PARADIM Materials Innovation Platform in-house program). Electron microscopy performed at the Cornell Center for Materials Research was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DMR-1719875.

Access to data and software codes is provided through the PARADIM Data Collective at data.paradim.org and the corresponding DOIs 10.34863/gbra-0060, and 10.34863/ssmm-2j11, as well as the corresponding code 10.5281/zenodo.4659690.